In the second chapter of this work, Kierkegaard gets very serious. There is certainly a heavy tone throughout, but it is felt most strongly in this section.

For Kierkegaard it is not an option to will one thing. Not something we are at liberty to choose if it happens to suit us. For Kierkegaard, it is one’s duty to will one thing. Not to do so is a moral failure before God. Not to do so is good old fashioned sin.

Within the world’s contemplative traditions there are various ways to look at what needs to be overcome in the process of spiritual transformation. One common, probably the most common, lens is that of personal “attachment/craving” – we crave and are attached to things in the external world (or even internal realities, often concepts we have about ourselves), things that we get our life from but which are ultimately temporary, without substance, illusory, impermanent. Breaking those attachments (in some traditions, in order to be attached ultimately to God) leads to liberation – part of which includes the release of the “selfless self,” one’s “Buddha Nature,” etc. The language of attachment and craving is characteristically Buddhist, but also finds expression in the Christian contemplative tradition, for instance in the writings of St. John of the Cross.

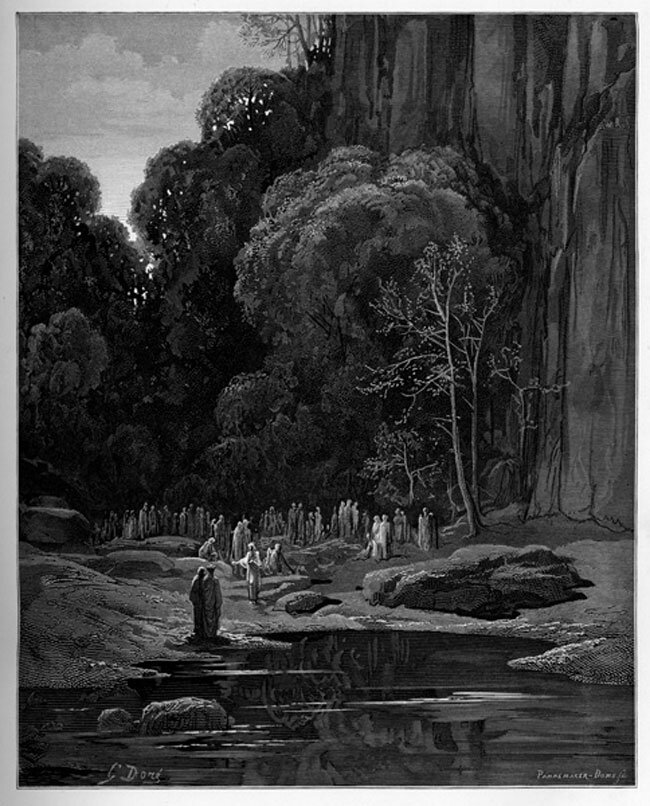

Another lens to look at what needs to be overcome is the lens of sin. It is our sin, our moral failure, that stands in the way of liberation. We must repent and turn from that sin in order to find God. One thinks of Dante climbing the Mountain of Purgatory in The Divine Comedy, passing those who are being purified of the sins they have committed in life. Kierkegaard is first and foremost a Christian, and the themes of sin, guilt, repentance, and forgiveness are never far away.

Interpreting the path through the lens of sin and repentance lends to a feeling of weight, of sobering, a sense of seriousness. It adds a moral dimension to the contemplative quest. We are morally obligated to turn away from our biased self-will towards the Good. Feel the difference, for instance, between saying “repent of your vanity” vs. “lose your attachment to your vanity.”

In Chapter 2, Kierkegaard speaks mainly of two guides – remorse and repentance – which should bring us back to the Good. If we are honest with ourselves, if we unflinchingly look at our lives, remorse should lead to a feeling of guilt, in turn leading to repentance and a turning back to the Good.

“There is, then, something which should at all times be done. There is something which in no temporal sense shall have its time. Alas, and when this is not done, when it is omitted, or when just the opposite is done, then once again, there is something (or more correctly it is the same thing, that reappears, changed, but not changed in its essence) which should at all times be done. There is something which in no temporal sense shall have its time. There must be repentance and remorse.

One dare not say of repentance and remorse that it had its time; that there is a time to be carefree and a time to be prostrated in repentance. Such talk would be: to the anxious urgency of repentance – unpardonably slow; to the grieving after God – sacrilege; to what should be done this very day, in this instant, in this moment of danger – senseless delay. For there is indeed danger. There is a danger that is called delusion. It is unable to check itself. It goes on and on: then it is called perdition. But there is a concerned guide, a knowing one, who attracts the attention of the wanderer, who calls out to him that he should take care. That guide is remorse. He is not so quick of foot as the indulgent imagination, which is the servant of desire. He is not so strongly built as the victorious intention. He comes on slowly afterwards. He grieves. But he is a sincere and faithful friend. If that guide’s voice is never heard, then it is just because one is wandering along the way of perdition. For when the sick man who is wasting away from consumption believes himself to be in the best of health, his disease is at the most terrible point. If there were someone who early in life steeled his mind against all remorse and who actually carried it out, nevertheless remorse would come again if he were willing to repent even of this decision. So wonderful a power is remorse, so sincere is its friendship that to escape it entirely is the most terrible thing of all.”

There is nothing “contemplative” here outside of a yearning for a self (sometimes called the selfless-self, Buddha nature, Atman/Brahman, True Self, the Holy Spirit/Christ working within) that is committed only to the Good. This is good old fashioned Christian preaching.

The contemplative practices, if one is so inclined, can be seen as “means of grace” for unlocking this self. This is something Kierkegaard doesn’t touch on, so far as I see, in this work.